by Mats Melin and Jennifer Schoonover

ISBN 9780367489472 Published December 31, 2020 by Routledge 284 Pages 43 B/W Illustrations

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Dance-Legacies-Scotland-True-Orchy/

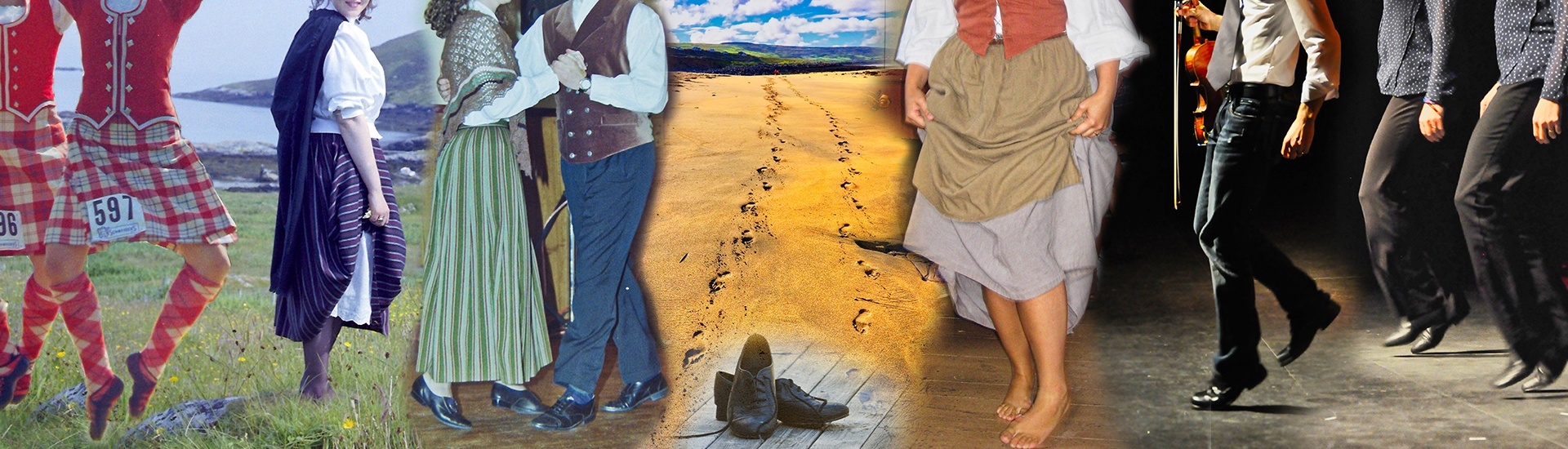

Dance Legacies of Scotland—Recollections of Percussive Step Dance in Scotland compiles a collage of references portraying percussive Scottish dancing and explains what influenced a wide disappearance of hard-shoe steps from contemporary Scottish practices.

Mats Melin and Jennifer Schoonover explore the historical references describing percussive dancing to illustrate how widespread the practice was, by giving some glimpses of what it looked and sounded like. Furthermore, the authors also explain what influenced a wide disappearance of hard-shoe steps from Scottish dancing practices. Their research draws together fieldwork, references from historical sources in English, Scots, and Scottish Gaelic, and insights drawn from the authors’ practical knowledge of dances. They portray the complex network of dance dialects that existed in parallel across Scotland, and share how remnants of this vibrant tradition have endured in Scotland and the Scottish diaspora to the present day.

This book will be of interest to scholars and students of Dance and Music and its relationship to the history and culture of Scotland.

Table of Contents

Introduction 1. ‘I wish I had it in my power to describe to you’: introductory observations on Step dance and its place in Scotland 2. From regional variations to standardisation of vernacular dance 3. Na brògan dannsaidh/The dancing shoes: foot anatomy, footwear, and body posture 4. Gaelic references and continental European connections 5. From Hornpipes to High Dances: historical terms and overlapping usage 6. Hyland step forward: eighteenth-century accounts 7. A few more flings and shuffles: nineteenth-century accounts, 1800–1839 8. Aberdeenshire to the Hebrides: nineteenth-century accounts, 1840–1899 9. Breakdown: twentieth-century accounts 10. An t-Seann Dùthaich: dancing in the Scottish diaspora 11. First-hand Step dance encounters and recollections in Scotland from the 1980s to 2016 collected by Mats Melin 12. Weaving the steps to the music 13. Echoes and reflections

Author Biographies

Mats Melin is a Lecturer Emeritus in Dance at the University of Limerick, Ireland (2005-2021). He has worked and performed extensively in Angus, Sutherland, the Scottish Highlands, the Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland, promoting Scottish traditional dance in schools and communities.

Jennifer Schoonover is a dancer and choreographer. She teaches movement principles, improvisation, dance pedagogy, and dance modalities including Cape Breton Step, Ceilidh, Highland, and Scottish Country dancing.

Reviews

”This important and timely publication addresses intriguing and long-unanswered questions concerning historical and recent practices of percussive step dancing in Scotland. Co-authors Mats Melin and Jennifer Schoonover possess excellent credentials to pursue and interrogate legacies of dancing in Scotland. As scholar practitioners with long and extensive experience of Scottish dance forms, they bring complementary knowledge and authority to the subject. Details of embodied memories of step-dancing drawn from Mats Melin’s fieldwork conducted in Scotland from the 1980s to 2016 reveal vestiges of a once familiar practice that was submerged and often dismissed. In summary, this is an important contribution to dance scholarship and an accessible text for those interested in percussive dancing and in Scottish culture and history.” Folk Music Journal, Theresa Jill Buckland, University of Roehampton, London.

“This important book addresses a key issue in the history of Scottish dance: the part played by percussive dancing in which the sounds of the feet match the music. Melin and Schoonover have amassed a huge amount of evidence for this style as a main thread running through Scottish dancing for the past 400 years. They rely not only on scholarly research, but also on first-hand authority based on Schoonover’s work as a Boston-based teacher and dancer and Melin’s extensive experience as Dance Development Officer for the Scottish Traditions of Dance Trust.

Percussive dancing as illustrated in this book is frequently performed in hard shoes and can be improvisatory. Heuching and finger snaps may accompany sounds made by the feet. Melin and Schoonover believe that percussive dancing lost its prominence in Scotland because of the Victorian preference for a smoother and more ‘genteel’ style of dancing. This was followed by the rise of standardizing organizations like the RSCDS and the Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing which both promoted a balletic style and soft-soled shoes. Despite denials by some Scots that Cape Breton step dancing with its strong percussive and improvisatory style had originally come from Scotland, through encounters in several parts of Scotland Melin was able to elicit traces of a similar style within living memory.

Rather than ‘tradition’, the authors use the term ‘legacies’ to emphasize the diversity and constant evolution of dancing practices and the creative contributions of many people who danced, taught, or influenced others. In keeping with that approach, they give details about many individuals, and extensive quotations which convey the excitement and vigour of this dance form.

Included in the book are thorough discussions of the anatomy of the foot, footwear historically used for dancing in Scotland, posture/stance, and surfaces for dancing. The language applied to step dancing is also critically analyzed: words used to classify step dances and dance music, and words used for the elements of a dance including onomatopoeic terms. Terms like ‘fleup’, ‘fleg’, and ‘skiff’ may be obscure to us now, but fortunately key terms like ‘treble’ and ‘shuffle’ have come down in unbroken transmission.

Readers may be surprised to learn that Scottish step dancing may not be indigenous in origin. Drawing on Gaelic sources found by the scholar Michael Newton, the authors trace the percussive style and quick, precise footwork to the 17th century Highlands. Through contacts with mainland Europe, the Gaelic élite absorbed Renaissance ideals of courtly dancing as a display of social grace, dexterity, and control. Rhythmic dancing on a wooden floor was especially valued. This style of dancing, though often with bare feet on bare earth, became typical of all Highlanders and was picked up by dancing masters like Francis Peacock of Aberdeen.

Country dancers may also be surprised to learn that (as previously documented by Tom and Joan Flett) the percussive style of ‘treepling’ or beating out the rhythm with the feet once extended to popular dances like ‘Petronella’ in some parts of rural Scotland. They are described as danced mainly by men wearing ‘tackety’ (hobnailed) boots. Generally, Scottish country dancers may feel that the book does less than justice to our own form of Scottish dancing. We have kept energy and excitement, together with rhythmic emphasis, through our response to enlivening Scottish music. In this part of the world at least, heuching and rhythmic handclapping can erupt, especially when we dance to live music. Also, the practical advantages of standardization for a worldwide form of dance may be implied in the book but are not stated.

One minor quibble: In the heading ‘Mr John McGill, dancing master, Girvan, Ayrshire, 1752’ the authors follow George Emmerson in one of his hasty assumptions. True, the dance manuscript summarized in a brief Notes and Queries article in 1953 and the full McGill manuscript recently given to the RSCDS Archive overlap in content, but they are not the same. The John McGill of the full MS is identified on its title page as ‘dancing master of Dunse’ – he was not the fiddler of Girvan. However, the overall point that percussive step dance was in the repertoire of a southern Scottish dancing master is valid. This MS also shows that a native flavour was appearing in the country dance in the mid-18th century, as it includes Scots terms like ‘oxter’ and ‘cleek’.

The authors refer to the ‘active exchange of dances and fashions particularly between France, England, and Scotland’ in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It would be interesting to know What they make of the MS Contre-Danses à Paris 1818, probably a draft manual of Scottish dances, in English, written by a dancing master resident in Paris. It describes reel and strathspey steps using the balletic terminology of the newly popular quadrille, with three reel steps identical to the quadrille steps also described in the MS and the others very close. To indicate extra hops, the strathspey steps are described with compounds like ‘strath-assemblé’ and ‘strath-sissonne’, reflecting the author’s characterization of the strathspey as ‘strictly national and peculiar to Scotland’. Is this an attempt to transfer the dignity and prestige of the ballroom quadrille to the traditional Scottish steps, while asserting stylistic differences?

Perhaps because it comes from just south of the Border, the evocative description of Scottish dancing in a letter by the poet John Keats is not included. He watched a country dancing school at Carlisle and note his use of the term ‘scotch’. ‘[They kickit & jumpit with mettle extraordinary, & whiskit, & fleckit, & toe’d it, & go’d it, & twirld it, & wheel’d it, & stampt it, & sweated it, tattooing the floor like mad; The difference between our country dances & these scotch figures is about the same as leisurely stirring a cup o’ tea & beating up a batter pudding.”

Rosemary Coupe, Vancouver, RSCDS Magazine, October 2022.

Dr Michael Newton’s Review of Dance Legacies of Scotland, IRSS 47, 2022